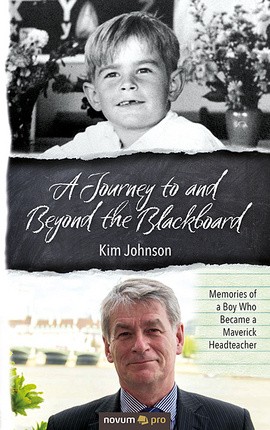

Medicine and Other Topics

Alistair Tulloch

GBP 16,90

GBP 13,99

Format: 13.5 x 21.5 cm

Number of Pages: 164

ISBN: 978-3-99131-561-2

Release Date: 05.04.2023

Dr. AJ Tulloch’s Medicine and Other Topics is an autobiography from someone steeped in the values of the NHS. This entertaining read offers vivid insights into Britain’s social and political life, both past and present from a compassionate, long-serving, GP.

Introduction

The idea of writing a book in the form of an autobiography crossed my mind several times in the last fifteen years only to be discarded despite the fact that I had done quite well at school. I had later written a number of medical articles and a chapter in several textbooks, but I did not feel confident about this task.

Nevertheless, it was my wife Christine who set the ball rolling again by pointing out three years ago suggesting that I ought to write a small booklet describing the variety of interesting tasks I have handled as a doctor. It was designed to entertain offspring, grandchildren and close friends. I gave some thought to this view, but I remained uncertain and as a result took no action.

However sometime later I read a book by Adam Kay, an obstetrician, called “This is Going to Hurt” which was an interesting read and a bestseller. He has much more talent than me but I am indebted to him as he changed my mind and I started to write the book. It set out to be purely an autobiography.

My career and lifestyle have been unusual to say the least and six months after graduating I was in the RAF which took me to Egypt and the Sudan. I was then a bachelor and I decided to spend two years on three hospital appointments. I never once met another GP who had done this length of postgraduate training at this stage. GPs today however would be unimpressed since they spend around four years or so in hospital and general practice while in postgraduate training. The result is that they are better trained today.

During my career I also wrote a thesis for my MD on structured records which seemed to interest only a few GPs. Subsequently, at a conference, I met the director of a computer company who said that if all GPs had introduced a structured record system the National Health Service could have saved millions. I advised the Ministry of Health about this but they took no action. I was twice invited abroad to speak on records – at a Conference of the Italian Epidemiological Society in Rome and at the University of Los Angeles on Care of the Elderly. In the last quarter of my career I began to take a special interest in care of people in advanced old age along with a colleague, Dr David Beale, a very able clinician. We approached all the relevant Colleges but were unable to provoke any interest. Retirement came when I was 61 years of age and we bought a house in Spain which we retained for fourteen years. Thereafter we have enjoyed a variety of foreign cruises. Finally the book touches on political affairs.

I have now been retired for 31 years as compared with 37 years in practice. I still kept fit playing tennis and golf and I believe that there is still a little petrol left in the tank. Now at the age of 96 I am really quite fit despite my having aortic stenosis (a leaking heart valve). However, I am much more forgetful these days though I am still enjoying life and am still playing golf.

On the other hand the final curtain cannot be too far away. I really cannot complain as life has been very kind to me from my early days with my parents and sister. Later and most important of all with my dear wife Christine, my three children and five grandchildren. Finally I have had a circle of friends whose company also gave me great pleasure although most of them are now dead.

So the reader can see how fortunate I have been working in general practice and on retirement my wife and I visiting so many fascinating foreign countries as well as delightful cruises especially on the rivers of Europe. Now the holidays are scaled down for obvious reasons.

Chapter 1 - Brief Ancestry of the Tulloch Family

My ancestors, whom I traced back to 1790, were based in the village of Kiltarlity, near Beauly in Invernesshire. They were poor Highland crofters who eked out a living from their modest plots of land. However, when my grandfather, Alexander Tulloch, married towards the end of the 19th century he moved to a croft called Ballachraggen in Kirkhill, a scattered village some seven miles from Inverness. There he built the family house himself and raised three children, the eldest of whom was my father, born in 1900. The tradition in the Highlands of Scotland at that time was that the first-born son took his father’s name and thus my father was also called Alexander to conform to this custom as had the previous three generations.

He had one brother and one sister, both close to him in age. Father was quite the most able of the three and having passed his exams he wanted to be a doctor but the family could not afford the costs involved. Instead he started training as a bank clerk with the Commercial Bank of Scotland (CBS) in Muir-of-Ord near Inverness, in 1916.

Then, in 1918 near the end of the war he was called up for military service and spent over two years mainly with the Army of Occupation in Germany.

On his return from the army he was transferred to a branch of the bank in Castletown, near Thurso in Caithness as a medium level bank clerk. Castletown was a pleasant little village laid out, unusually for Scotland, in a modest grid pattern. Father was very happy there although the work was scarcely demanding – he started at 10 am and usually finished around 3.30 to 4pm, after which he might have some bookwork to do. However the social life in the village was very lively. Remarkably the village had two halls with plenty of scope for village social events, dances and sports such as badminton, while the Bank Manager had a private lawn tennis court – courtesy of the Commercial Bank of Scotland.

Soon after father arrived he met Bill McKenzie and they became friends. Bill ran a village butcher’s business and was also an auctioneer. He lived in Castletown and was well off even if he was rather laid back about business affairs. He confided this to my father and asked him to help with his financial affairs. Dad was delighted and he soon re-organised them but refused to be paid as ‘the bank wouldn’t like it’ which became a family joke. However Bill, who was a very generous man, insisted in rewarding father with sides of beef, lamb and chicken breast and legs etc. He also introduced father to his sister Mary and they soon began courting. She was the daughter of the now retired village butcher John McKenzie – my grandfather – who had a thriving butcher’s business delivering meat to people living within a 30-mile radius of Castletown as well as supplying the village itself. Grandpa (then retired) was a real character with a great fund of amusing stories which made him excellent company for my cousin John McKenzie (son of Bill) and myself. When not at work he often wore a grey Homburg hat and a black coat which made him look more like a city gent than a village butcher.

Grannie was much more serious but nonetheless devoted to her children. They had a family of six – four sons and two daughters, the elder being my mother Mary, a woman of strong convictions, a wicked sense of humour and who was something of an entertainer. She also used a number of local dialect words, many of which I had never heard before – she said that they were “old Caithness words” which in most cases was true but she would occasionally simply fashion words of her own. The younger daughter was called Margaret – always known as Mag – also a woman of strong convictions and the brightest intellect in their home. She wanted to be a doctor and she had qualified for Edinburgh University before she was 17 but they did not take applicants aged below 18 so she deferred. She had always been good at sports and she played hockey and tennis and ultimately reached near county status. However she kept deferring the medical course and ultimately gave up on the subject. Instead she turned to gym teaching which was a surprise to everyone but she enjoyed the work and did a bit of coaching as well.

Two of her brothers, Bob and Jack emigrated to the USA and later Canada some years before the First World War. They ended up running a thriving cattle dealing business in Lacombe, Alberta, Canada. By the middle twenties they were very prosperous. Another brother, Bill (mentioned before), took over the running of the butcher’s shop with a manager and he also served as an auctioneer as well as managing two farms, Castle Hill and Greenvale. Mind you, with his various forms of work he had to delegate much of the day-to-day farm work to employees. Thus he acted rather like a gentleman farmer.

The last brother had a serious accident before the Great War which left him almost permanently in pain and, as a result, he was declared unfit for military service. However he insisted that he was fit and he persuaded the Army to accept him. The Army however was to make no concessions to his disability except that that he was not to be a fighting soldier. As a result he was obliged to do long hours on the parade ground ‘square bashing’. In addition, he was not exempt from having to carry around heavy equipment and keeping fit just like a fighting soldier. As a result he suffered much more pain and he was a sick man on discharge from the service. As a result, tragically, he was to die in 1922. He had always been known as the ‘iron man’ of the McKenzie family.

My mother, Mary Mackenzie and her parents had been crofters, but one of my grandfather’s brothers drank the family out of the croft. However, her father, John McKenzie, immediately set up as a butcher, serving Castletown and about 30 miles around. He quite steadily built up the business across the years and by the time I was going there in the late twenties he had retired. Of all my grandparents he was the one I liked most although my grannie was very kind to my cousin John McKenzie and me as well. We were up to all sorts of mischief but she saved us from punishment time and again.

Chapter 2 - My Early Years

In due course Father married Mary McKenzie and within a year I was born on May 31st, 1926, in Manu House, a big house built by a retired sea captain years before – the rather odd name came from somewhere in China as he had worked mainly in the Orient. The house was divided into flats, one of which was all my parents could afford in the twenties. The great event of this era was the General Strike, which had created an upheaval some weeks earlier in 1926. There was also the matter of what name I was to be given since Mother had found Alexander ‘rather a mouthful’ but she did not want to offend the Tullochs. So she settled for Alistair – the Gaelic for Alexander and only a little less of a mouthful.

Perth 1927

A year later in 1927 Father was transferred to the Perth branch of the Bank and promoted from bank clerk to ‘accountant’ which was a bank ranking in those days rather than the financial affairs professional of today.

Stow, Midlothian 1928

After a year there we moved to Stow, a lovely village on the river Gala about 26 miles from Edinburgh. There Dad was to be a bank manager and he was told he was the youngest in the CBS, but to begin with he was under the surveillance of the manager from a bigger branch in nearby Galashiels – it was however a largely nominal supervision. Father incidentally was aged 27 at this point and we came to live in a bigger house than either of my parents had experienced before, part of which was the bank office. They thought they had landed in clover, especially as they had a large garden and father was a keen gardener. We were to spend twelve happy years there and looking back I feel that no children could have been more fortunate than my sister and I to live in such an attractive area with devoted parents and a lively social life. I joined the village gang of boys and we soon got up to the usual forms of mischief. We were also very interested in football, rugby and tennis which I started playing at the age of nine.

Primary School Stow, Midlothian 1933

I recall clearly starting school in Stow and I particularly remember the first day at school for two reasons. There was a world map on the wall, almost half of which was coloured in red to identify parts of the British Empire and of course at the age five I had no idea what an empire was. After school I also tripped on the kerb later that first day and gashed my knee which required stitches not given in most cases at that time. I can recall this episode quite clearly today nearly ninety years afterwards because of the acute pain when the needle went through the skin on each side of the cut. Nonetheless I really enjoyed my time at Stow school and I nearly always came first in the class, which led me to believe I was more able than was the case. Of course most of my fellow pupils came mainly from a more modest background than me and were rarely strong performers, probably as they did not have parents encouraging them to ‘stick in’ as mine did. Stow was a commuter village for those who worked in Edinburgh and there were a good few more affluent families there than ours. Their children were usually privately educated in Edinburgh and so we saw them much less often than the locals. Incidentally the private school system in Scotland differs from the English public school system since most of the private pupils are non-resident and based mainly in the bigger cities or nearby. However there are also some four or five residential private schools in various parts of the country based on the English school system, which catered for wealthy families, the aristocracy and even the odd member of the Royal Family. Incidentally I knew very little about the English educational system before I came down to England in 1950 to do my National Service in the RAF. I was simply bewildered by the cost especially of the most expensive ‘public schools’ like Eton and Harrow – I put the term in inverted commas as nothing on earth seemed to me to be less public than a public school.

Stow was in the middle of a fertile area of Scotland and my impression was that the farmers in the district were more prosperous than in many other parts of Scotland. However my father claimed that the Black Isle (near Inverness) provided the best farming soil in Scotland, a view contested by several other Scots friends. Dad was a proud Highlander and not always highly objective on matters of this sort but he was the most encouraging of fathers.

I was active in the local group of boys and we were up to every mischief under the sun but sometimes things went too far. On one occasion I was the perpetrator and to this day I feel a sense of guilt when the subject comes up. Although I was a small boy I suffered very little from bullying at school but one boy in the class used to ‘ping’ my ears, which was very humiliating in company. I asked him to stop but he paid no attention and since he was much bigger than me there was little I could do about it. So I decided to give him a good soaking in the hope that he would end the ‘pinging’. This was to be achieved by dropping a flat stone near him as he emerged from under a bridge on which I was seated. He had been fishing for minnows with four of our friends. Now as the stone left my hand, to my horror he moved to the right towards the falling stone which clipped him on the side of the head opening a cut which bled freely and friends on the spot came to his assistance. To my shame I rushed home hoping that I would avoid retribution but my Mother soon recognised that something was amiss. So I had to explain what had happened and by this time the boy had turned up at our house seeking help. Mother dressed his wound and took him to the doctor who put in a couple of stitches. On her return she gave me ‘two of the best’ on each hand adding ‘you deserved more’. Next day came the second half of the punishment – the headmaster hauled me out in front of the school and criticised me for cowardly behaviour in dropping the stone and (even worse) departing the scene after the accident. He then added: ‘You might easily have seriously injured or even killed Archie’, which was of course quite true and I felt terribly guilty. I even considered running away as I did not seem to have a friend in the world at this point. So I had nobody to run to for support. Mind you, in another three days I was back in favour as one of the boys again.

We were a lively class, given sometimes to whispering or even occasionally chattering in lessons, which did not go down at all well with the teachers and occasionally they resorted to punishment with a thick leather belt with thongs, known to the pupils as “the belt” or “the tawse” or “the tug”, administered to the hands. Of course nobody wanted this punishment but anyone who had it became a class hero and thus it did have the desired result. In due course teachers recognised this and resorted instead to expelling the offender from class which was much more effective. The reason for this was that one felt very lonely outside the class door and there was always the fear that the headmaster would come along and ask why the expulsion had been ordered. This often led to the importance of not making the teacher’s job more difficult but if he felt that the offence was more serious the belt was used as punishment administered sometimes by the headmaster himself in his room.

My time in Stow, from 1928 to 1940, was, in retrospect, a real pleasure to me and I made a series of friends with whom I played a variety of sports – football and a rather tame form of rugby in the winter, and in the summer a crude form of cricket as well as fishing for minnows in the Gala River, which also deepened in one place enabling us to use it for swimming. We even started to play tennis in 1935 and I was to play the game for the next 70 years. As I now look back down the years, my impression is that the summers in the thirties were almost eternally warm and sunny enabling us to enjoy these pleasures: Or is it simply distance lending enchantment to the view?

The arrival of my sister Margaret 1935

Nineteen thirty-five saw the arrival of my sister Margaret after a difficult pregnancy for Mother who had severe and persistent sickness known to the medical profession as hyperemesis gravidarum – doctors have a weakness for imposing names. Then she went from bad to worse and the doctors warned my father that she may die unless she was admitted to a private ward in hospital. There the doctors tried everything and they did slow the rate of decline. However Mother was becoming concerned about the steadily mounting costs of private inpatient hospital care, which Father could ill afford. As a result she suddenly announced that she was going home, to the dismay of the doctors including her GP, in whom she normally had great faith. They told her that if she did go home she was much more likely to die. Her response was simply to say: ‘If I am going to die I would prefer to die at home rather than in hospital’. Poor Father by this time was broken hearted since there was no sign of improvement and he felt sure she was going to die. However she proved both him and the doctors wrong as she turned the corner and began to improve slowly some three to four days after her return. Thereafter the recovery continued slowly but steadily and she had a normal delivery some six months later, a baby girl weighing eight and half pounds. I fear it must be said that I viewed her arrival with mixed feelings since I alone had been the centre of attention for the previous nine years and this state of affairs was now coming to an end.

The idea of writing a book in the form of an autobiography crossed my mind several times in the last fifteen years only to be discarded despite the fact that I had done quite well at school. I had later written a number of medical articles and a chapter in several textbooks, but I did not feel confident about this task.

Nevertheless, it was my wife Christine who set the ball rolling again by pointing out three years ago suggesting that I ought to write a small booklet describing the variety of interesting tasks I have handled as a doctor. It was designed to entertain offspring, grandchildren and close friends. I gave some thought to this view, but I remained uncertain and as a result took no action.

However sometime later I read a book by Adam Kay, an obstetrician, called “This is Going to Hurt” which was an interesting read and a bestseller. He has much more talent than me but I am indebted to him as he changed my mind and I started to write the book. It set out to be purely an autobiography.

My career and lifestyle have been unusual to say the least and six months after graduating I was in the RAF which took me to Egypt and the Sudan. I was then a bachelor and I decided to spend two years on three hospital appointments. I never once met another GP who had done this length of postgraduate training at this stage. GPs today however would be unimpressed since they spend around four years or so in hospital and general practice while in postgraduate training. The result is that they are better trained today.

During my career I also wrote a thesis for my MD on structured records which seemed to interest only a few GPs. Subsequently, at a conference, I met the director of a computer company who said that if all GPs had introduced a structured record system the National Health Service could have saved millions. I advised the Ministry of Health about this but they took no action. I was twice invited abroad to speak on records – at a Conference of the Italian Epidemiological Society in Rome and at the University of Los Angeles on Care of the Elderly. In the last quarter of my career I began to take a special interest in care of people in advanced old age along with a colleague, Dr David Beale, a very able clinician. We approached all the relevant Colleges but were unable to provoke any interest. Retirement came when I was 61 years of age and we bought a house in Spain which we retained for fourteen years. Thereafter we have enjoyed a variety of foreign cruises. Finally the book touches on political affairs.

I have now been retired for 31 years as compared with 37 years in practice. I still kept fit playing tennis and golf and I believe that there is still a little petrol left in the tank. Now at the age of 96 I am really quite fit despite my having aortic stenosis (a leaking heart valve). However, I am much more forgetful these days though I am still enjoying life and am still playing golf.

On the other hand the final curtain cannot be too far away. I really cannot complain as life has been very kind to me from my early days with my parents and sister. Later and most important of all with my dear wife Christine, my three children and five grandchildren. Finally I have had a circle of friends whose company also gave me great pleasure although most of them are now dead.

So the reader can see how fortunate I have been working in general practice and on retirement my wife and I visiting so many fascinating foreign countries as well as delightful cruises especially on the rivers of Europe. Now the holidays are scaled down for obvious reasons.

Chapter 1 - Brief Ancestry of the Tulloch Family

My ancestors, whom I traced back to 1790, were based in the village of Kiltarlity, near Beauly in Invernesshire. They were poor Highland crofters who eked out a living from their modest plots of land. However, when my grandfather, Alexander Tulloch, married towards the end of the 19th century he moved to a croft called Ballachraggen in Kirkhill, a scattered village some seven miles from Inverness. There he built the family house himself and raised three children, the eldest of whom was my father, born in 1900. The tradition in the Highlands of Scotland at that time was that the first-born son took his father’s name and thus my father was also called Alexander to conform to this custom as had the previous three generations.

He had one brother and one sister, both close to him in age. Father was quite the most able of the three and having passed his exams he wanted to be a doctor but the family could not afford the costs involved. Instead he started training as a bank clerk with the Commercial Bank of Scotland (CBS) in Muir-of-Ord near Inverness, in 1916.

Then, in 1918 near the end of the war he was called up for military service and spent over two years mainly with the Army of Occupation in Germany.

On his return from the army he was transferred to a branch of the bank in Castletown, near Thurso in Caithness as a medium level bank clerk. Castletown was a pleasant little village laid out, unusually for Scotland, in a modest grid pattern. Father was very happy there although the work was scarcely demanding – he started at 10 am and usually finished around 3.30 to 4pm, after which he might have some bookwork to do. However the social life in the village was very lively. Remarkably the village had two halls with plenty of scope for village social events, dances and sports such as badminton, while the Bank Manager had a private lawn tennis court – courtesy of the Commercial Bank of Scotland.

Soon after father arrived he met Bill McKenzie and they became friends. Bill ran a village butcher’s business and was also an auctioneer. He lived in Castletown and was well off even if he was rather laid back about business affairs. He confided this to my father and asked him to help with his financial affairs. Dad was delighted and he soon re-organised them but refused to be paid as ‘the bank wouldn’t like it’ which became a family joke. However Bill, who was a very generous man, insisted in rewarding father with sides of beef, lamb and chicken breast and legs etc. He also introduced father to his sister Mary and they soon began courting. She was the daughter of the now retired village butcher John McKenzie – my grandfather – who had a thriving butcher’s business delivering meat to people living within a 30-mile radius of Castletown as well as supplying the village itself. Grandpa (then retired) was a real character with a great fund of amusing stories which made him excellent company for my cousin John McKenzie (son of Bill) and myself. When not at work he often wore a grey Homburg hat and a black coat which made him look more like a city gent than a village butcher.

Grannie was much more serious but nonetheless devoted to her children. They had a family of six – four sons and two daughters, the elder being my mother Mary, a woman of strong convictions, a wicked sense of humour and who was something of an entertainer. She also used a number of local dialect words, many of which I had never heard before – she said that they were “old Caithness words” which in most cases was true but she would occasionally simply fashion words of her own. The younger daughter was called Margaret – always known as Mag – also a woman of strong convictions and the brightest intellect in their home. She wanted to be a doctor and she had qualified for Edinburgh University before she was 17 but they did not take applicants aged below 18 so she deferred. She had always been good at sports and she played hockey and tennis and ultimately reached near county status. However she kept deferring the medical course and ultimately gave up on the subject. Instead she turned to gym teaching which was a surprise to everyone but she enjoyed the work and did a bit of coaching as well.

Two of her brothers, Bob and Jack emigrated to the USA and later Canada some years before the First World War. They ended up running a thriving cattle dealing business in Lacombe, Alberta, Canada. By the middle twenties they were very prosperous. Another brother, Bill (mentioned before), took over the running of the butcher’s shop with a manager and he also served as an auctioneer as well as managing two farms, Castle Hill and Greenvale. Mind you, with his various forms of work he had to delegate much of the day-to-day farm work to employees. Thus he acted rather like a gentleman farmer.

The last brother had a serious accident before the Great War which left him almost permanently in pain and, as a result, he was declared unfit for military service. However he insisted that he was fit and he persuaded the Army to accept him. The Army however was to make no concessions to his disability except that that he was not to be a fighting soldier. As a result he was obliged to do long hours on the parade ground ‘square bashing’. In addition, he was not exempt from having to carry around heavy equipment and keeping fit just like a fighting soldier. As a result he suffered much more pain and he was a sick man on discharge from the service. As a result, tragically, he was to die in 1922. He had always been known as the ‘iron man’ of the McKenzie family.

My mother, Mary Mackenzie and her parents had been crofters, but one of my grandfather’s brothers drank the family out of the croft. However, her father, John McKenzie, immediately set up as a butcher, serving Castletown and about 30 miles around. He quite steadily built up the business across the years and by the time I was going there in the late twenties he had retired. Of all my grandparents he was the one I liked most although my grannie was very kind to my cousin John McKenzie and me as well. We were up to all sorts of mischief but she saved us from punishment time and again.

Chapter 2 - My Early Years

In due course Father married Mary McKenzie and within a year I was born on May 31st, 1926, in Manu House, a big house built by a retired sea captain years before – the rather odd name came from somewhere in China as he had worked mainly in the Orient. The house was divided into flats, one of which was all my parents could afford in the twenties. The great event of this era was the General Strike, which had created an upheaval some weeks earlier in 1926. There was also the matter of what name I was to be given since Mother had found Alexander ‘rather a mouthful’ but she did not want to offend the Tullochs. So she settled for Alistair – the Gaelic for Alexander and only a little less of a mouthful.

Perth 1927

A year later in 1927 Father was transferred to the Perth branch of the Bank and promoted from bank clerk to ‘accountant’ which was a bank ranking in those days rather than the financial affairs professional of today.

Stow, Midlothian 1928

After a year there we moved to Stow, a lovely village on the river Gala about 26 miles from Edinburgh. There Dad was to be a bank manager and he was told he was the youngest in the CBS, but to begin with he was under the surveillance of the manager from a bigger branch in nearby Galashiels – it was however a largely nominal supervision. Father incidentally was aged 27 at this point and we came to live in a bigger house than either of my parents had experienced before, part of which was the bank office. They thought they had landed in clover, especially as they had a large garden and father was a keen gardener. We were to spend twelve happy years there and looking back I feel that no children could have been more fortunate than my sister and I to live in such an attractive area with devoted parents and a lively social life. I joined the village gang of boys and we soon got up to the usual forms of mischief. We were also very interested in football, rugby and tennis which I started playing at the age of nine.

Primary School Stow, Midlothian 1933

I recall clearly starting school in Stow and I particularly remember the first day at school for two reasons. There was a world map on the wall, almost half of which was coloured in red to identify parts of the British Empire and of course at the age five I had no idea what an empire was. After school I also tripped on the kerb later that first day and gashed my knee which required stitches not given in most cases at that time. I can recall this episode quite clearly today nearly ninety years afterwards because of the acute pain when the needle went through the skin on each side of the cut. Nonetheless I really enjoyed my time at Stow school and I nearly always came first in the class, which led me to believe I was more able than was the case. Of course most of my fellow pupils came mainly from a more modest background than me and were rarely strong performers, probably as they did not have parents encouraging them to ‘stick in’ as mine did. Stow was a commuter village for those who worked in Edinburgh and there were a good few more affluent families there than ours. Their children were usually privately educated in Edinburgh and so we saw them much less often than the locals. Incidentally the private school system in Scotland differs from the English public school system since most of the private pupils are non-resident and based mainly in the bigger cities or nearby. However there are also some four or five residential private schools in various parts of the country based on the English school system, which catered for wealthy families, the aristocracy and even the odd member of the Royal Family. Incidentally I knew very little about the English educational system before I came down to England in 1950 to do my National Service in the RAF. I was simply bewildered by the cost especially of the most expensive ‘public schools’ like Eton and Harrow – I put the term in inverted commas as nothing on earth seemed to me to be less public than a public school.

Stow was in the middle of a fertile area of Scotland and my impression was that the farmers in the district were more prosperous than in many other parts of Scotland. However my father claimed that the Black Isle (near Inverness) provided the best farming soil in Scotland, a view contested by several other Scots friends. Dad was a proud Highlander and not always highly objective on matters of this sort but he was the most encouraging of fathers.

I was active in the local group of boys and we were up to every mischief under the sun but sometimes things went too far. On one occasion I was the perpetrator and to this day I feel a sense of guilt when the subject comes up. Although I was a small boy I suffered very little from bullying at school but one boy in the class used to ‘ping’ my ears, which was very humiliating in company. I asked him to stop but he paid no attention and since he was much bigger than me there was little I could do about it. So I decided to give him a good soaking in the hope that he would end the ‘pinging’. This was to be achieved by dropping a flat stone near him as he emerged from under a bridge on which I was seated. He had been fishing for minnows with four of our friends. Now as the stone left my hand, to my horror he moved to the right towards the falling stone which clipped him on the side of the head opening a cut which bled freely and friends on the spot came to his assistance. To my shame I rushed home hoping that I would avoid retribution but my Mother soon recognised that something was amiss. So I had to explain what had happened and by this time the boy had turned up at our house seeking help. Mother dressed his wound and took him to the doctor who put in a couple of stitches. On her return she gave me ‘two of the best’ on each hand adding ‘you deserved more’. Next day came the second half of the punishment – the headmaster hauled me out in front of the school and criticised me for cowardly behaviour in dropping the stone and (even worse) departing the scene after the accident. He then added: ‘You might easily have seriously injured or even killed Archie’, which was of course quite true and I felt terribly guilty. I even considered running away as I did not seem to have a friend in the world at this point. So I had nobody to run to for support. Mind you, in another three days I was back in favour as one of the boys again.

We were a lively class, given sometimes to whispering or even occasionally chattering in lessons, which did not go down at all well with the teachers and occasionally they resorted to punishment with a thick leather belt with thongs, known to the pupils as “the belt” or “the tawse” or “the tug”, administered to the hands. Of course nobody wanted this punishment but anyone who had it became a class hero and thus it did have the desired result. In due course teachers recognised this and resorted instead to expelling the offender from class which was much more effective. The reason for this was that one felt very lonely outside the class door and there was always the fear that the headmaster would come along and ask why the expulsion had been ordered. This often led to the importance of not making the teacher’s job more difficult but if he felt that the offence was more serious the belt was used as punishment administered sometimes by the headmaster himself in his room.

My time in Stow, from 1928 to 1940, was, in retrospect, a real pleasure to me and I made a series of friends with whom I played a variety of sports – football and a rather tame form of rugby in the winter, and in the summer a crude form of cricket as well as fishing for minnows in the Gala River, which also deepened in one place enabling us to use it for swimming. We even started to play tennis in 1935 and I was to play the game for the next 70 years. As I now look back down the years, my impression is that the summers in the thirties were almost eternally warm and sunny enabling us to enjoy these pleasures: Or is it simply distance lending enchantment to the view?

The arrival of my sister Margaret 1935

Nineteen thirty-five saw the arrival of my sister Margaret after a difficult pregnancy for Mother who had severe and persistent sickness known to the medical profession as hyperemesis gravidarum – doctors have a weakness for imposing names. Then she went from bad to worse and the doctors warned my father that she may die unless she was admitted to a private ward in hospital. There the doctors tried everything and they did slow the rate of decline. However Mother was becoming concerned about the steadily mounting costs of private inpatient hospital care, which Father could ill afford. As a result she suddenly announced that she was going home, to the dismay of the doctors including her GP, in whom she normally had great faith. They told her that if she did go home she was much more likely to die. Her response was simply to say: ‘If I am going to die I would prefer to die at home rather than in hospital’. Poor Father by this time was broken hearted since there was no sign of improvement and he felt sure she was going to die. However she proved both him and the doctors wrong as she turned the corner and began to improve slowly some three to four days after her return. Thereafter the recovery continued slowly but steadily and she had a normal delivery some six months later, a baby girl weighing eight and half pounds. I fear it must be said that I viewed her arrival with mixed feelings since I alone had been the centre of attention for the previous nine years and this state of affairs was now coming to an end.